Our Nervous System’s Role in Pain

The nervous system plays a central role in how we experience pain, acting as the communication highway between the body and the brain. Pain doesn’t just live in the body, it is processed, interpreted, and sometimes even amplified by the brain and nervous system.

When the body detects something potentially harmful, like an injury, illness, or even stress, sensory nerves send signals to the spinal cord and up to the brain. The brain then decides whether or not these signals indicate a threat and whether to create the experience of pain. This is an important protective mechanism. However, in chronic pain, this system can become overly sensitive or “stuck in alarm mode,” continuing to send pain signals even when there’s no longer damage or danger present.

This is where the central nervous system (CNS), made up of the brain and spinal cord, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls the body’s stress and relaxation responses, come into play. When we’re constantly in a state of stress, fear, or hypervigilance, the brain may interpret normal sensations as dangerous, amplifying pain signals and making the body more reactive.

In chronic pain, the nervous system can essentially become “wired for protection” instead of balance, keeping the body in a heightened state of alert. Healing often involves retraining the nervous system through techniques like Vagus nerve activation, breathwork, mindfulness, or grounding techniques to shift from danger to safety, helping the brain learn that the pain is no longer needed as a warning signal.

Our goal is to help our nervous system have a healthy titration of shifting form alert to rest and digest. The more we learn how to turn on the parasympathetic state, the quicker our nervous system will shift to this place when facing alerts that are no longer threats. This leads to better heart rate variability and improves our overall well-being as well lowering the danger signals.

Key Roles:

Regulate the Automatic Nervous Sytem

Shift Away From High Alert And Hyper-vigilant State.

Have a healthy titration from sympathetic to parasympathetic.

Integrate grounding techniques like breathwork, mindfulness, forest bathing.

Intercept pro-longed anxiety.

Find moments of down-time throughout our day.

Recognize the signals of being overwhelmed.

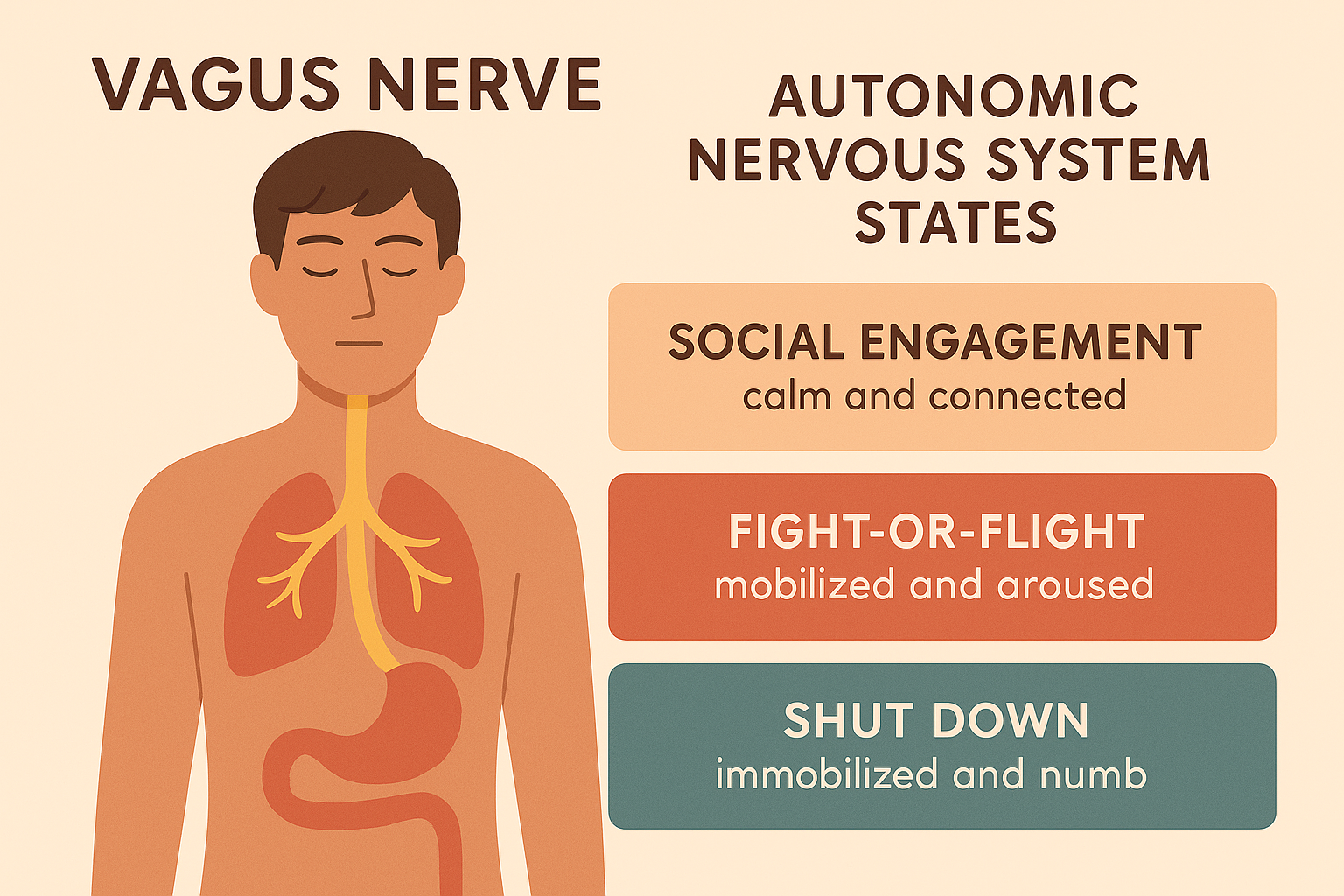

PolyVagal Theory

According to Polyvagal Theory, we move between the three nervous system states—ventral vagal (safe/social), sympathetic (fight/flight), and dorsal vagal (freeze/shut down)—in response to how our body perceives safety or threat. These shifts happen automatically, but with awareness and practice, we can learn to influence them and help guide ourselves back to a regulated state.

3 Nervous System States

Ventral Vagal (Safe and Social):

This is the state of safety, connection, and regulation. When we're here, we feel calm, open, grounded, and able to engage with others.Sympathetic (Fight or Flight):

This is the mobilized state. When the body senses threat, it prepares to take action—your heart rate increases, muscles tense, and your focus narrows. You might feel anxious, restless, or angry.Dorsal Vagal (Freeze or Shut Down):

When a threat feels overwhelming or inescapable, the body can go into shutdown. You may feel numb, disconnected, fatigued, or hopeless.

How We Move Between States:

From Sympathetic (Fight/Flight) to Ventral Vagal (Calm/Safe):

Use grounding tools like deep breathing (especially long exhales or 4-7-8 breath)

Try gentle movement like walking, stretching, or shaking out tension

Practice mindfulness or somatic tracking

Connect with someone you trust—a conversation, eye contact, or even a smile can help

Use safety mantras: “I am safe. I can handle this.”

From Dorsal Vagal (Freeze/Shutdown) to Ventral Vagal (Calm/Safe):

Start small, begin with noticing sensations or wiggling fingers and toes

Use warmth (blanket, warm drink, hand on heart) to gently reawaken the body

Try rhythmic, soothing stimulation like humming, rocking, or tapping

Engage in activities that offer gentle stimulation without overwhelm (petting a cat, looking at nature)

Connect to another person or a memory of connection

From Dorsal to Sympathetic (Reactivation):

Sometimes we need to pass through sympathetic activation before returning to safety. For example, coming out of shutdown may involve a burst of energy or anxiety. This is normal—it’s your nervous system mobilizing to move. From there, you can use calming practices to transition into ventral vagal.